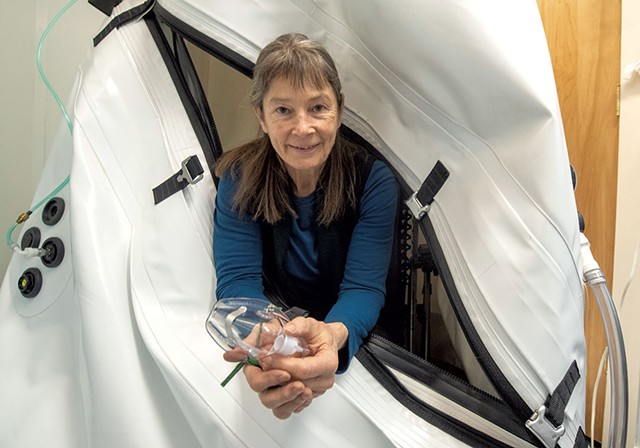

Merin Perretta’s chiropractor suggested she try Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) to help with her long-COVID symptoms. Merin, a 46-year-old integrative counselor, thought “This must be too good to be true”. But oxygen combined with pressure is not too good to be true; and HBOT has been found to have extreme benefit in relieving the symptoms of long-COVID.

Three days a week, Perretta visited Hyperbaric Vermont, a nonprofit health care facility in Montpelier. There, she spent roughly an hour reclined in an enclosed plastic chamber roughly the length of a pool table, exposed to concentrated levels of oxygen under higher-than-normal atmospheric pressure.

Though it took several weeks before she noticed any improvement, Perretta eventually called the results “a total game changer in my life.” The annoying cough finally subsided, as did other, more serious complaints she’d lived with for years.

For two decades, Perretta suffered from posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome, commonly called “chronic Lyme.” Many of its symptoms — body aches, extreme fatigue, and cognitive impairment or “brain fog” — are similar to those experienced by patients with long COVID. An estimated 45 percent of patients who recover from COVID-19 experience symptoms that last four months or more, according to a study published in December in the medical journal the Lancet.

“Hyperbaric didn’t cure me,” Perretta cautioned, “but it supported my body in such a way that it’s been able to get on top of the COVID and the Lyme.”

Perretta is among an increasing number of Vermonters who are using HBOT to relieve their long COVID. Originally developed as a therapy for deep-sea divers experiencing decompression sickness, aka “the bends,” HBOT has become what one local provider called “the last stop” for patients with treatment-resistant ailments. Chief among them: long COVID and Lyme.

Many of Vermont’s medical professionals are either unaware of these uses of HBOT or are skeptical of its touted benefits due to the dearth of U.S.-based studies on its effectiveness. But HBOT advocates point to mounting evidence from other countries showing it offers many patients significant and lasting relief.

People have used pressurized environments to treat maladies since the 1600s, when Anglo-Irish philosopher and physicist Robert Boyle first began experimenting with them. By the mid-1900s, military physicians were using hyperbaric chambers to treat divers sickened by gas embolisms or the bends. Currently, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration has approved the use of HBOT for 14 medical conditions, including carbon monoxide poisoning, radiation burns, crush injuries, skin graft complications, and nonhealing wounds and ulcers.

Treatment of neither long COVID nor chronic Lyme are on the FDA’s list of approved uses. Nevertheless, hyperbaric chambers, which were once available only in large hospitals and burn centers, have found their way into community outpatient clinics, where they’re commonly used to treat those and other ailments. The FDA considers HBOT “off label” — that is, legal only with a doctor’s prescription — for treating multiple sclerosis, strokes, Crohn’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue and traumatic brain injuries.

“It was the beginning of getting my life back.” GRACE JOHNSTONE (JEB WALLACE-BRODEUR)

In Vermont, Dr. Grace Johnstone has long championed the use of HBOT. The East Hardwick chiropractor is nationally certified in undersea and hyperbaric medicine and is the founder, president and medical director of Hyperbaric Vermont, which has offices in South Burlington and Montpelier. She has also trained independent practitioners in Middlebury, Brattleboro and West Lebanon, N.H., in the use of HBOT.

Johnstone first tried HBOT herself after contracting Lyme disease in July 2012, which led to meningitis and radiculoneuritis, an inflammation of the roots of the spinal nerves. These conditions left her incapacitated and unable to walk, read, drive or work for nearly a year.

But after Johnstone began using a hyperbaric chamber in April 2013, most of her symptoms subsided. As she told Seven Days in 2017, “For me, it was the beginning of getting my life back.”

Since then, Johnstone’s mission has been to make HBOT available to any Vermonter who needs it, regardless of their ability to pay. Because no Vermont insurance companies will cover off-label uses of HBOT, she founded Hyperbaric Vermont as a way to make treatments more affordable for her patients. In a hospital setting, HBOT can cost thousands of dollars. Hyperbaric Vermont charges patients $62 to $65 per visit, depending on the number of visits; the nonprofit fundraises to cover the full expense of its hyperbaric services.

How does HBOT work? The combination of increased pressure and concentrated oxygen levels has potent physiological effects, Johnstone explained. HBOT acts as a natural antimicrobial and healing agent that helps normalize the body’s immune functions. Several studies have shown that HBOT has anti-inflammatory effects on muscles, tissues, joints and organs. In the brain, it can stimulate the growth of new nerves and blood vessels.

Traditional hyperbaric chambers, such as those found in hospitals, typically use 100 percent oxygen at 2.4 atmospheres. Normal room air is 21 percent oxygen, and normal pressure at sea level is 1 atmosphere.

By contrast, Hyperbaric Vermont’s HBOT chambers are set no higher than 1.3 atmospheres with an oxygen level between 93 and 97 percent. The lower pressure and oxygen level are just as effective therapeutically, Johnstone noted, and also minimize the risk of complications, such as lung and sinus damage, vision loss, inner ear problems, and oxygen toxicity. An added benefit is that the lower oxygen level eliminates the danger of fires or explosions from static charges, thus allowing patients to use electronic devices while in the chamber.

Beyond its FDA-approved uses, HBOT has long been considered an alternative, even fringy treatment method. But in the past few years, its value for other ailments has attracted attention in a range of medical settings, including at U.S. military hospitals. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs began offering HBOT to combat veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars who had treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder. Many of those vets, who’d been injured by roadside explosives, initially sought HBOT to relieve their TBI symptoms but subsequently saw improvements in their PTSD, as well.

HBOT has also shown promise in the treatment of anxiety and depression. A study published in the July 2017 issue of the journal Medicine found that patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries who underwent HBOT had “significantly lower” levels of anxiety and depression than patients who didn’t use the treatment. Johnstone noted that Hyperbaric Vermont, as well as the organization’s flagship practice, Community Hyperbaric in East Hardwick, routinely sees patients who use it to manage their anxiety and depression.

When Seven Days first wrote about HBOT in 2017, most local physicians interviewed for the story were either unfamiliar with its off-label uses or questioned its alleged benefits. Dr. Peter Moses, a now-retired gastroenterologist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, was dubious that HBOT could benefit patients with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s or irritable bowl disorders, calling it “a technology that has been searching for a clinical niche for some time.” Similarly, Dr. Joe McSherry, a UVM Medical Center neurologist, called it “a fairly harmless placebo.”

Not much has changed since then. Dr. David Kaminsky, a pulmonary and critical care physician at UVM Medical Center and a professor in the Larner College of Medicine, routinely sees patients with long COVID symptoms. In fact, he’s currently involved in a yearlong study of the lung functions of 50 long COVID sufferers, many of whom still have breathing problems.

In an email, Kaminsky wrote that he knows of no patients or medical colleagues who have used HBOT to treat long COVID. But he urged patients to exercise caution when trying any non-FDA-approved therapies, which may be costly, have only a placebo effect or distract from other underlying causes of their symptoms.

“But I certainly understand that many people are desperate to feel better, so as long as their eyes are wide open to these caveats, they certainly have every right to explore some of these new, potentially useful therapies,” Kaminsky added. “It looks like HBOT is relatively safe, and there is biological rationale to support it being helpful.”

Johnstone isn’t surprised that more Vermont physicians aren’t aware of HBOT’s potential uses. Only five medical schools in the country teach hyperbaric therapy, she noted, and it’s only offered as an elective.

“Our physicians are trained in and rely heavily on pharmaceuticals,” she said. And, because the FDA review process is time-consuming and costly, there’s little incentive for corporations or individual practitioners to seek federal approval of HBOT’s off-label uses.

Perretta wasn’t surprised, either. She said she was “not a heavy user” of the mainstream medical establishment, in large part because of her experiences with trying to treat chronic Lyme.

“I felt gaslit all the time,” she said. “Going to them became an exercise in my own frustration.”

But HBOT is the one treatment that’s made a measurable difference. Over the past month, Perretta has reduced the frequency of her hyperbaric sessions from three days a week to just once a week, and she expects to scale back further to every other week.

“Honestly, there’s not a doubt in my mind that hyperbaric will, at some point, be covered by insurance … because it is so effective,” she added. “The truth is stronger than their skepticism.”

Cited by Seven Days VT